Sizing a home battery based on your average daily usage from a utility bill is the most common and costly mistake made in the UK.

- Instantaneous power demand (kW), not just total energy capacity (kWh), dictates whether your high-draw appliances like kettles and showers will actually function.

- UK winter solar generation is often negligible; capacity must be calculated for grid-charging arbitrage and storm resilience, not just storing daytime sun.

Recommendation: Conduct a granular, peak-load energy audit to understand your true power requirements before investing a single pound.

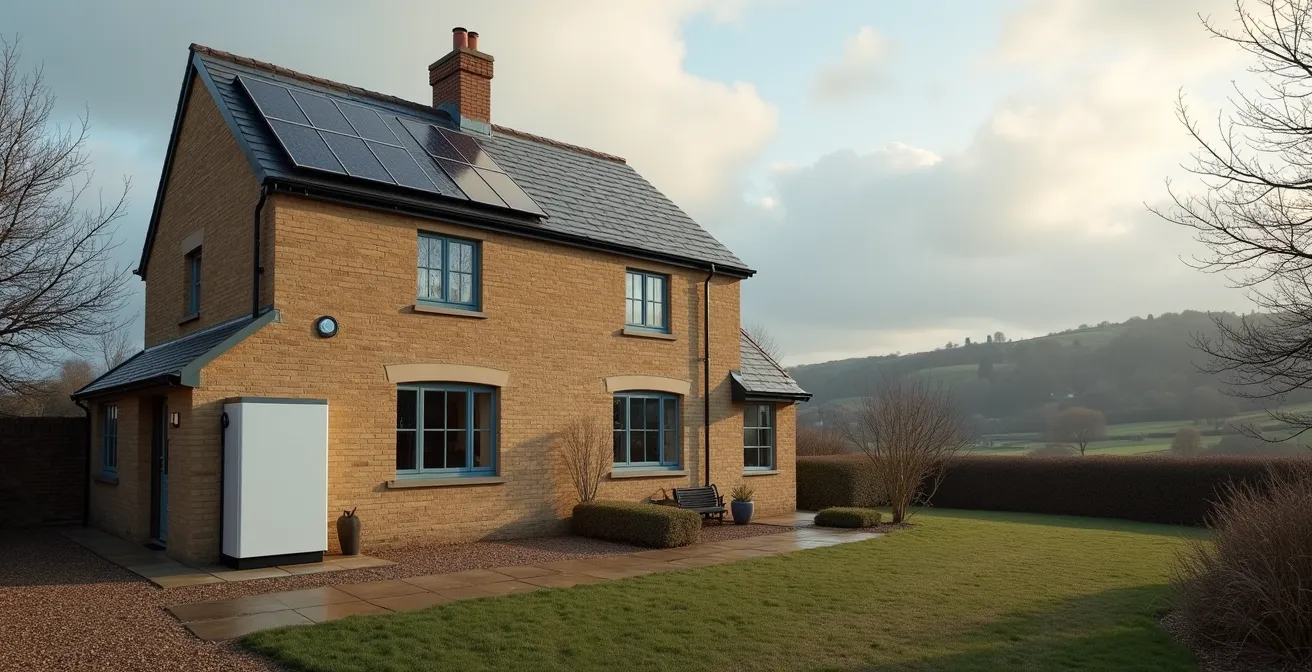

For rural homeowners and preppers across the UK, the goal of energy independence is a pragmatic response to increasingly unreliable grids and volatile energy prices. The core component in any resilience strategy is the battery storage system. However, a fundamental misunderstanding is leading to expensive and inadequate installations. The common approach is to look at an annual electricity bill, divide by 365, and buy a battery to match that “average” daily figure. This method is dangerously flawed.

The calculation for 24-hour autonomy isn’t about average energy use; it’s a strategic calculation of peak power demand, seasonal deficits, and long-term asset degradation. Simply buying a 10kWh battery because your daily average is 9kWh ignores the critical moment you need to run a 3kW kettle and a 10kW shower simultaneously. The system fails not from a lack of stored energy (kWh), but from an inability to deliver the required instantaneous power (kW).

This article moves beyond simplistic averages. We will dissect the critical difference between energy and power, audit your true consumption patterns, and evaluate the hardware choices that determine genuine off-grid capability. The objective is to equip you with a calculator’s mindset, enabling you to specify a system that provides true resilience during a multi-day winter storm, not just one that looks good on paper during a sunny afternoon in July.

To navigate these critical calculations effectively, this guide is structured to address each variable in the off-grid equation. Explore the sections below to build a comprehensive understanding of how to correctly size your battery system for genuine UK conditions.

Summary: Calculating True Battery Capacity for UK Off-Grid Living

- Why Can’t Your 5kWh Battery Boil the Kettle and Run the Shower?

- How to Audit Your Daily kWh Usage Before Buying a Battery?

- Modular vs All-in-One Batteries: Which Is Better for Future Expansion?

- The Cycle Life Truth: How Much Capacity Will Be Left After 10 Years?

- How to Utilize Your Battery Capacity in December When Solar Is Zero?

- How Many Panels Do You Need to Charge an EV and Run a Heat Pump?

- The Oil Boiler Ban: What Are the Options for Rural Properties?

- Why Is a Battery Storage System Essential Even Without Solar Panels?

Why Can’t Your 5kWh Battery Boil the Kettle and Run the Shower?

The most frequent and frustrating failure of undersized battery systems stems from a confusion between energy capacity (measured in kWh) and power output (measured in kW). Your 5kWh battery might hold enough *energy* to run a 3kW kettle for 1.6 hours, but that’s irrelevant. The real question is: can the system’s inverter deliver 3kW of *power* instantaneously? If you then switch on a 10kW electric shower, you are demanding a total of 13kW from the system. This is the instantaneous power demand.

Most standard battery systems are paired with a 5kW inverter. When your home’s demand exceeds this 5kW limit, the system trips and shuts down to protect itself, plunging you into darkness despite the battery being fully charged. The battery’s kWh capacity is a measure of the fuel in the tank; the inverter’s kW rating is the size of the fuel pipe. For a resilient UK home, the pipe is often more critical than the tank. Typical peak loads for common appliances reveal the scale of the problem: an electric kettle requires a 2.5-3kW instant draw, and a powerful electric shower can demand a 7.5-10.5kW continuous load. An evening peak with a microwave, shower, and kettle running can easily exceed 12kW, far beyond the capability of a standard setup.

Therefore, the first calculation is not your total consumption, but identifying your maximum simultaneous power draw. Your inverter must be rated to handle this peak load, or the system is functionally useless for genuine off-grid living.

How to Audit Your Daily kWh Usage Before Buying a Battery?

Basing your battery size on an annual electricity bill is a critical error because it averages out huge seasonal variations. Real-world data shows the extent of this discrepancy; UK households exhibit significant seasonal variation, with winter consumption being over 50% higher than in summer. An audit must be granular, capturing the peaks and troughs of your specific lifestyle, not a national average. A proper energy audit is a forensic accounting of your power usage, broken down by hour and by season.

The goal is to build a detailed load profile. This involves identifying three key figures: your baseload (the minimum power your home consumes 24/7, like fridges and routers), your morning peak (typically 6-9 am), and your crucial evening peak (4-8 pm). These figures will be drastically different between a winter weekend and a summer weekday. This detailed data, which can be gathered from your smart meter’s In-Home Display (IHD) or dedicated plug-in monitors, is the only reliable basis for sizing a battery. Simply relying on the annual average will leave you with a massive energy deficit in the depths of winter.

Your Action Plan: A Step-by-Step Energy Audit Method

- Access your smart meter’s IHD for real-time consumption data.

- Log your home’s hourly kW usage for one full winter weekend and one summer weekday to capture different patterns.

- Note the separate consumption figures for the morning peak (6-9 am) and evening peak (4-8 pm).

- Calculate your ‘base load’ by checking the minimum consumption reading, usually between 2-4 am.

- Use plug-in energy monitors to measure the exact draw of high-consumption appliances like heat pumps or immersion heaters.

- Add a 20% buffer to your calculated daily total for future-proofing, especially considering a typical UK EV adds around 2,400kWh annually.

Only with this detailed profile can you begin to calculate the kWh capacity required to service your actual lifestyle through a 24-hour period, especially during the high-demand, low-generation winter months.

Modular vs All-in-One Batteries: Which Is Better for Future Expansion?

Once you have an accurate load profile, the next calculation involves system architecture. The two dominant designs in the UK market are all-in-one units and modular systems. An all-in-one system, like a GivEnergy AIO, integrates the battery and inverter into a single, wall-mounted unit with a fixed capacity (e.g., 13.5kWh). A modular system, like those using Pylontech modules, allows you to start with a smaller capacity (e.g., 2.4kWh) and add more battery modules over time as your needs or budget change.

From a purely financial standpoint, modularity comes at a cost. Larger battery systems offer significant economies of scale, with MCS data showing installation costs falling dramatically per kWh as system size increases. Installing a large all-in-one system from the outset is often cheaper per kWh than starting small and expanding a modular system later. However, the all-in-one approach locks you into a fixed capacity and power output. If you later add an EV or a heat pump, your only option for expansion is to install another complete system in parallel, which can be complex and expensive.

The following table breaks down the key differences based on current UK market offerings:

| Feature | Modular (e.g., Pylontech) | All-in-One (e.g., GivEnergy AIO) |

|---|---|---|

| Initial Capacity | 2.4kWh minimum | 13.5kWh fixed |

| Expansion Method | Add modules (up to 16 units) | Limited to 6 systems parallel |

| UK Installation Cost | £500-800 per module added | £7,000-8,000 complete |

| Space Requirements | Flexible rack mounting | Single wall-mount unit |

| G99 Application | May need resubmission | One-time approval |

The calculation is one of cost versus flexibility. An all-in-one system offers better initial value if your energy forecast is stable and accurate. A modular system provides expensive but invaluable flexibility if you anticipate significant increases in your future energy demand.

The Cycle Life Truth: How Much Capacity Will Be Left After 10 Years?

A battery’s advertised capacity is not the capacity you will have for its entire lifespan. All lithium-ion batteries suffer from degradation, a gradual loss of their ability to hold a charge with every cycle of charging and discharging. The industry standard warranty typically guarantees around 70-80% of original capacity after 10 years or a set number of cycles (usually 6,000-10,000). This means a 10kWh battery might only function as a 7kWh battery a decade later. For anyone planning for long-term resilience, this degradation factor must be part of the initial sizing calculation.

To ensure your system can still meet your 24-hour autonomy needs in year ten, you must build in a degradation buffer from day one. A conservative approach is to oversize your initial capacity by 20-30%. If your audit determines you need 10kWh of usable capacity for winter autonomy, you should be specifying a system of at least 12.5-13kWh. Interestingly, some manufacturers already account for this. Real-world data from a UK Tesla Powerwall owner shows minimal degradation after four years of daily use. Some newer units even ship with a higher-than-advertised capacity, effectively building in a buffer to absorb initial degradation while still meeting warranty specifications over the long term.

Ultimately, the true cost of a battery isn’t its purchase price, but its cost per kWh delivered over its entire functional lifespan. Sizing a system without accounting for degradation is a calculation that guarantees future failure.

How to Utilize Your Battery Capacity in December When Solar Is Zero?

For the UK prepper, December is the ultimate test case. Solar photovoltaic (PV) generation is often near zero for days on end. In this scenario, the battery’s function pivots from storing free solar energy to a tool for strategic tariff arbitrage. The goal is to use the grid as your power source but on your own terms. This involves charging the battery during the dead of night when electricity is cheap and discharging it to power your home during the expensive evening peak.

Agile time-of-use (ToU) tariffs, like those offered by Octopus Energy, are essential for this strategy. For example, the ‘Octopus Go’ tariff provides a four-hour window (e.g., 00:30-04:30) where electricity can cost as little as 7.5p/kWh. You program your system to fully charge during this cheap period. Then, during the evening peak (16:00-19:00), when grid electricity can cost over 40p/kWh, you switch your home to run entirely from the battery, effectively saving over 30p for every kWh used. This active management turns your battery from a passive storage unit into a dynamic financial asset.

The strategy can be refined further for maximum benefit:

- Set the battery to charge only during the cheapest overnight window.

- Program it to discharge and power the home during the 16:00-19:00 peak rate period.

- Maintain a 20-30% state of charge as an emergency buffer for unexpected power cuts.

- Enable grid export features to sell power back to the grid during high-demand ‘Saving Sessions’, where rewards can be substantial.

- Monitor agile pricing for rare ‘negative pricing’ events on very windy nights, where you are paid to take electricity from the grid.

In the context of a UK winter, the smartest battery isn’t the one connected to the most solar panels, but the one with the most intelligent software for exploiting grid price volatility.

How Many Panels Do You Need to Charge an EV and Run a Heat Pump?

The combination of an electric vehicle (EV) and an air-source heat pump represents the peak demand scenario for a modern UK household. This combination fundamentally changes the scale of any off-grid calculation. While an average home might use 9-10 kWh per day, UK homes with both an EV and a heat pump can face a combined daily load of 40-50kWh in winter. Attempting to service this demand with solar panels alone is, for most UK properties, a mathematical impossibility.

The limiting factor is roof space. A typical UK semi-detached house can accommodate between 10 and 14 solar panels, equating to a 3.5-5kWp (kilowatt-peak) system. Given the UK’s average annual solar yield, this system will generate approximately 3,000-4,250kWh over the entire year. The combined demand from the heat pump and EV, however, could be as high as 18,000kWh annually. The solar generation covers, at best, only 25% of the total need. The winter generation deficit is immense; on a dark December day, solar output will be virtually zero while demand from the heat pump is at its absolute maximum.

In this high-demand scenario, the battery’s role shifts entirely. It is no longer primarily for storing solar energy. Its main functions become:

- Absorbing the full, albeit small, solar generation during winter days to be used in the evening.

- Performing large-scale tariff arbitrage by charging its entire capacity from the grid overnight at low rates to offset the huge daytime and evening consumption of the heat pump.

- Providing the massive instantaneous power (kW) required to start the heat pump compressor and EV charger simultaneously.

Therefore, for an EV and heat pump owner, the battery capacity calculation must be based on the ability to time-shift this massive 40-50kWh daily load using the grid, not on the fantasy of being self-sufficient from a small rooftop solar array in winter.

The Oil Boiler Ban: What Are the Options for Rural Properties?

For rural properties currently reliant on oil boilers, the upcoming ban presents a significant challenge that intersects directly with energy resilience. The most common replacement, an air-source heat pump, transfers energy demand from an oil delivery to the electrical grid—a grid that can be particularly unreliable in exposed, rural locations. This makes a robust battery storage system not just an addition, but a core component of a viable heating solution. The primary calculation is ensuring you have enough stored energy to run the heat pump and other critical circuits through a typical 48-72 hour winter storm outage.

Fortunately, recent regulatory changes in the UK specifically address this need. The new PAS 63100-2024 standards now permit up to 80kWh of battery storage to be installed in external detached buildings like garages. This capacity is transformative for rural resilience. A system of this size allows a typical farmhouse to run a 12kW heat pump through extended winter outages while maintaining power to critical loads like pumps, refrigeration, and communications. The standard mandates strict safety protocols, including fire compartmentalization and ventilation, but it provides a clear pathway for achieving genuine, multi-day autonomy.

A resilience-focused setup for a rural property transitioning from oil should include:

- A minimum of 20kWh battery capacity specifically for heat pump backup.

- Black-start capability, allowing the system to restart itself from the battery alone after a total grid failure.

- A dedicated sub-panel for critical circuits, ensuring that stored energy is prioritized for essentials like heating controls and water pumps.

- Full compliance with PAS 63100-2024 ventilation and safety requirements for the battery location.

- Consideration of a hybrid approach, such as a biomass boiler whose pumps and fans are backed up by the battery.

The oil boiler ban forces a recalculation of home energy strategy. For rural properties, this calculation must prioritize long-duration autonomy, making a large, professionally specified battery system an indispensable investment.

Key Takeaways

- Your battery’s usability is defined by its inverter’s power (kW), not just its energy capacity (kWh). Peak demand is the critical metric.

- Accurate sizing requires a detailed audit of your seasonal and hourly usage, not an annual average from a bill.

- Long-term capacity must be oversized by 20-30% to account for inevitable battery degradation over 10 years.

Why Is a Battery Storage System Essential Even Without Solar Panels?

The concept of installing a home battery without any solar panels has rapidly shifted from a niche experiment to a mainstream financial strategy in the UK. This trend is driven by pure grid-based calculation: exploiting the vast price difference between off-peak and peak electricity. For a homeowner focused on resilience and cost reduction, a battery-only system offers a compelling and often faster return on investment than a full solar-and-battery setup, particularly in the solar-starved UK winters. As noted by industry experts Heatable UK, “Battery-only energy storage… has quickly gone from niche experiment to national trend.”

The business case is simple and powerful. A homeowner with a 10kWh battery on a time-of-use tariff can see significant savings. One UK-based case study shows annual savings of £550 by charging the battery at an 11p/kWh overnight rate and using that stored energy to avoid 40p+/kWh peak daytime rates. This creates a predictable payback period of around five years. The second function is resilience. For preppers and rural homeowners, this battery, kept charged by the grid, provides an uninterruptible power supply (UPS) for the entire home, guaranteeing continuity during the increasingly frequent storm-related outages.

This strategy is already being adopted at scale. It is estimated that approximately 10,000 UK households have already installed battery-only systems, a number that is growing rapidly as time-of-use tariffs become more common and the value of grid stability services increases. For these users, the battery is not an environmental statement; it is a cold, hard financial asset and an insurance policy against grid failure. It proves that the value of energy storage is intrinsic and not solely dependent on the presence of solar generation.

Therefore, the final calculation is one of opportunity. In the modern UK energy market, a battery’s primary value comes from its ability to manipulate time—buying low and using high. This function is entirely independent of the sun, making it a critical tool for any calculated resilience strategy.